August 2nd marked my second week aboard the R/V Pelican. This week was quite eventful! We completed the shelf-wide hypoxia survey cruise and demobilized, then we mobilized for the next cruise and set sail! We also got to do something really exciting during the period between the two cruises… but that’s for later. 😉

“Mobilizing” a research vessel relates to the process of preparing the vessel to fulfill the objectives of the research cruise. For example, for this shelf-wide hypoxia survey cruise, a safe boat was needed to complete dive ops (Yes, dive ops! More on that in a little bit!), so we had to load – and subsequently unload at the end of the cruise – a safe boat onto the back deck of the Pelican.

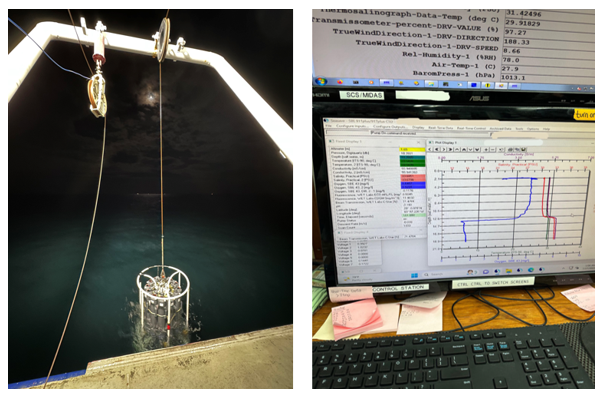

The latter portion of the shelf-wide hypoxia cruise, as I alluded to in the last blog post, involved transiting to stations East of the Mississippi River. It took us about 27 hours to complete this transit! There were 37 more stations that were completed. Again, I was not on shift for all of the stations as operations were occurring at all hours of the day. My shift was from 14:00 to 02:00 for the duration of this cruise. I was involved with the completion of 15 of the 37 stations. The same standard operating procedure (SOP) from the stations West of the Mississippi occurred at this set of stations – a CTD cast was performed, as well as the deployment of a Niskin bottle with an EOX3 Multiparameter Sonde Instrument attached.

In total during this cruise, 138 stations were completed! The time between stations on the transect lines varied between ~30 minutes to ~1 hour, and the time between transect lines was ~2-3 hours. In other words, this cruise felt very quick-paced.

After the Chief Scientist determined that we had surveyed all of the bounds of the hypoxic region, there was time for members of the science party to complete dive operations. The objective of these dive operations was to survey the diversity and abundance of native and invasive species on and surrounding the pilings of uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platforms. With these surveys, they were interested in seeing if there were differences in the species’ abundance and diversity in the regions above and below the hypoxic threshold (2 milligrams of Oxygen per liter of water).

The “order of events” that occurred to make sure the dive operations happened safely and successfully were:

-

The science party went through the stations sampled and picked sites based off of their oxygen and turbidity conditions, as well as their proximity to an uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform. The oxygen and turbidity conditions were measured using SBE 43 and transmissometer instruments attached to the CTD rosette.

-

After the stations with the desired criteria were chosen, we started to transit to each of the sites. Once a station was reached, members of both the crew and science party would look at the uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform that had been previously selected and decide if it was actually a safe place to dive off of. The safety of the structure was determined based on whether or not the safe boat (the small boat that would be used to motor divers to and from the dive site) would be able to tie off to it.

-

Once the platform was deemed safe, the science party, myself, and Maggie, my mentor, would check the ADCP data for how strong (and in what direction) currents were throughout the water column. We would also refer to the data that was being collected by the Knudsen Chirp (a type of echosounder) to see how deep the water was at these particular locations.

-

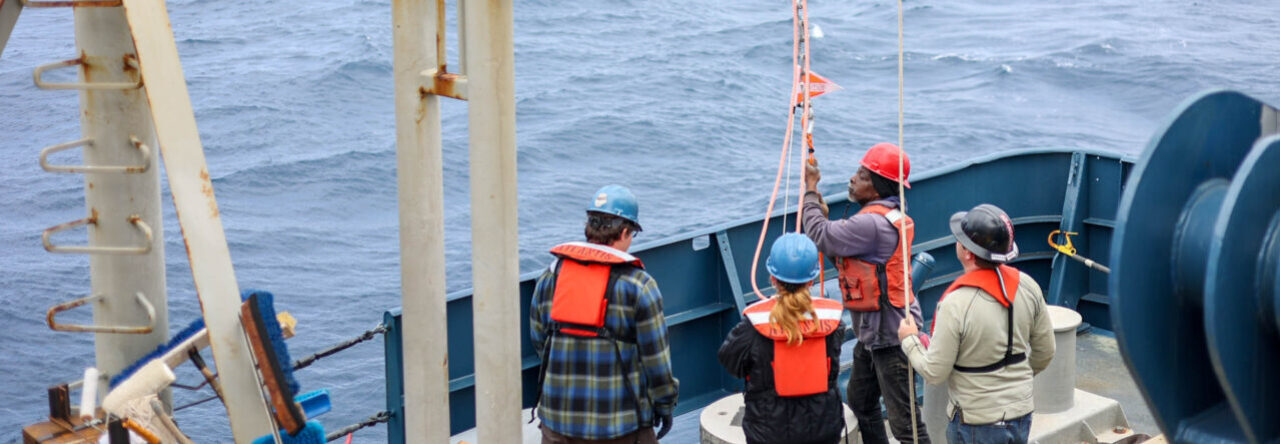

If currents were a safe speed, and the structure was safe to be tied to, we moved forward with the operation and would deploy the safe boat off the starboard side of Pelican. I helped with these deployments by running a tagline attached to either the bow or stern of the safe boat.

The science party went through the stations sampled and picked sites based off of their oxygen and turbidity conditions, as well as their proximity to an uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform. The oxygen and turbidity conditions were measured using SBE 43 and transmissometer instruments attached to the CTD rosette.

After the stations with the desired criteria were chosen, we started to transit to each of the sites. Once a station was reached, members of both the crew and science party would look at the uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform that had been previously selected and decide if it was actually a safe place to dive off of. The safety of the structure was determined based on whether or not the safe boat (the small boat that would be used to motor divers to and from the dive site) would be able to tie off to it.

Once the platform was deemed safe, the science party, myself, and Maggie, my mentor, would check the ADCP data for how strong (and in what direction) currents were throughout the water column. We would also refer to the data that was being collected by the Knudsen Chirp (a type of echosounder) to see how deep the water was at these particular locations.

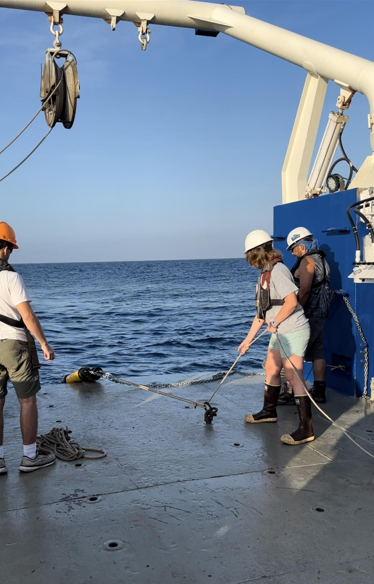

If currents were a safe speed, and the structure was safe to be tied to, we moved forward with the operation and would deploy the safe boat off the starboard side of Pelican. I helped with these deployments by running a tagline attached to either the bow or stern of the safe boat.

The safe boat about to be deployed.

-

After the safe boat was in the water, we would move it forward to the CTD deck and tie it off on cleats. Once it was secured, I would help load dive gear onto the small boat, and help the divers get in safely.

-

After everything (and everyone) was loaded, we would motor to the uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform, tie off to a piling, deploy the dive float, complete a safety briefing and go over dive plan, help the divers safely get into water, and hand them their gear.

After the safe boat was in the water, we would move it forward to the CTD deck and tie it off on cleats. Once it was secured, I would help load dive gear onto the small boat, and help the divers get in safely.

After everything (and everyone) was loaded, we would motor to the uncrewed fixed oil/natural gas platform, tie off to a piling, deploy the dive float, complete a safety briefing and go over dive plan, help the divers safely get into water, and hand them their gear.

My view from the safe boat that shows us tied up to the piling of an uncrewed oil/natural gas platform, and the divers about to start their descent.

-

While divers were down, Maggie and I kept watch for their bubbles to make sure that they were not drifting away from the structure.

-

Once the dive was completed, I helped divers load their gear and then get back into the safe boat.

-

We would then motor back to the Pelican, load dive gear back onto the back deck, and help the divers get out of the safe boat. Once the divers were safely back on the vessel, then I would get out and help with tag lining the safe boat back onto the back deck.

While divers were down, Maggie and I kept watch for their bubbles to make sure that they were not drifting away from the structure.

Once the dive was completed, I helped divers load their gear and then get back into the safe boat.

We would then motor back to the Pelican, load dive gear back onto the back deck, and help the divers get out of the safe boat. Once the divers were safely back on the vessel, then I would get out and help with tag lining the safe boat back onto the back deck.

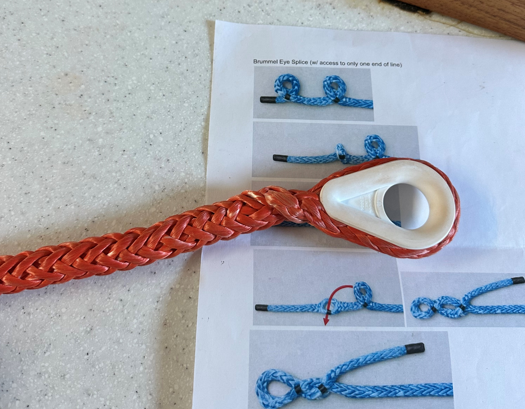

I was very excited to be a small boat co-operator as I have not been a part of this type of operation on previous cruises. These operations allowed me to practice: unit conversions (converting between knots and meters per second), operating taglines, tying knots, and radio communication skills. I also learned a lot about the logistics behind– and execution of– scientific dive operations.

Prior to this internship, I had only ever been on cruises that took place in the Northeast Pacific. Experiencing a different region of the ocean has been really fun. I had never seen oil rigs or so many large shipping vessels in person before. It’s a different world over here in the Gulf of Mexico!

The shelf-wide hypoxia cruise ended very early the morning of August 1st. It was cool to observe how the vessel gets tied up to the dock. There is a lot of communication and coordination that needs to happen before, during, and after this event happens. This was the first time I was able to see how a boat gets docked from the Bridge (where the Captain and Mate sit in order to operate the vessel), as well as watch the lines get thrown from the vessel to shore. After docking, we worked on demobilizing, as well as mobilizing for the next cruise. I helped with rigging and operating taglines on the equipment that was being offloaded.

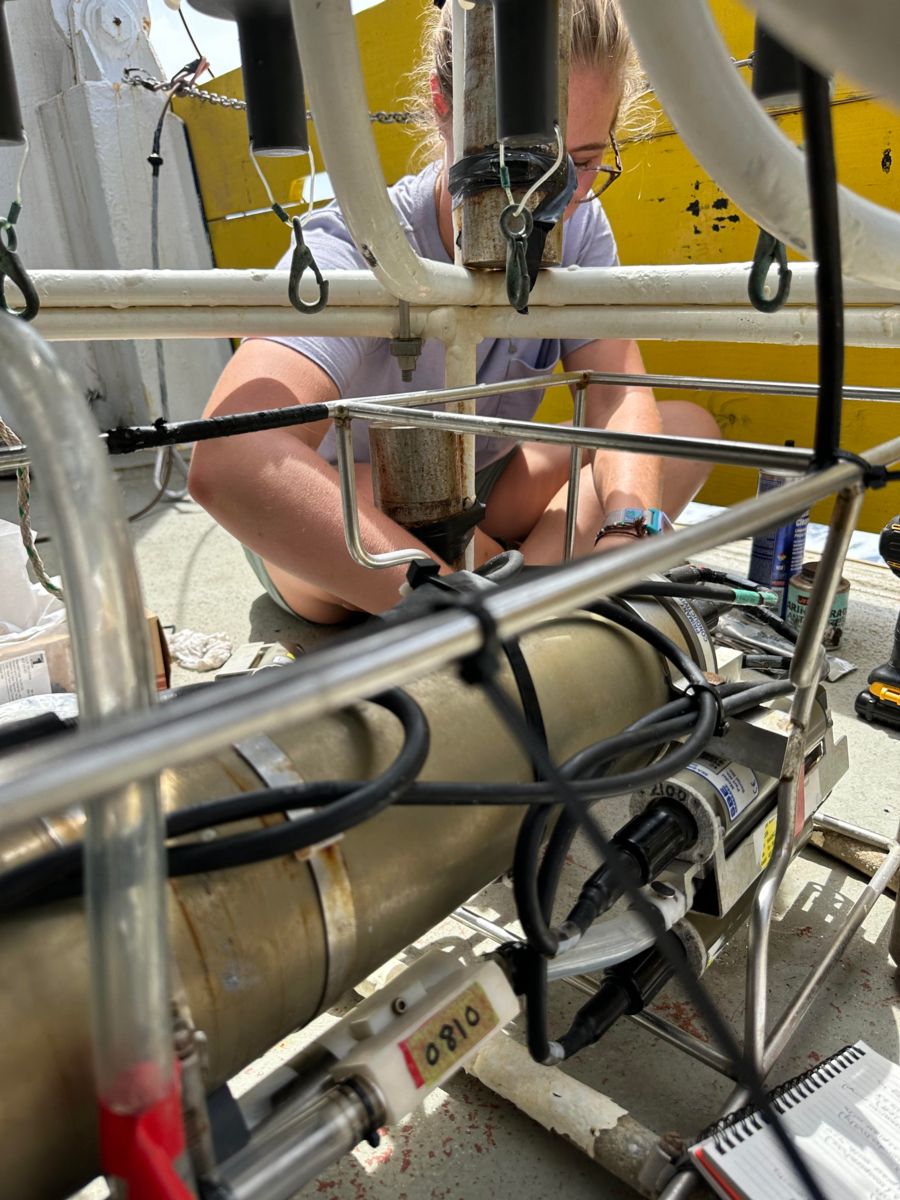

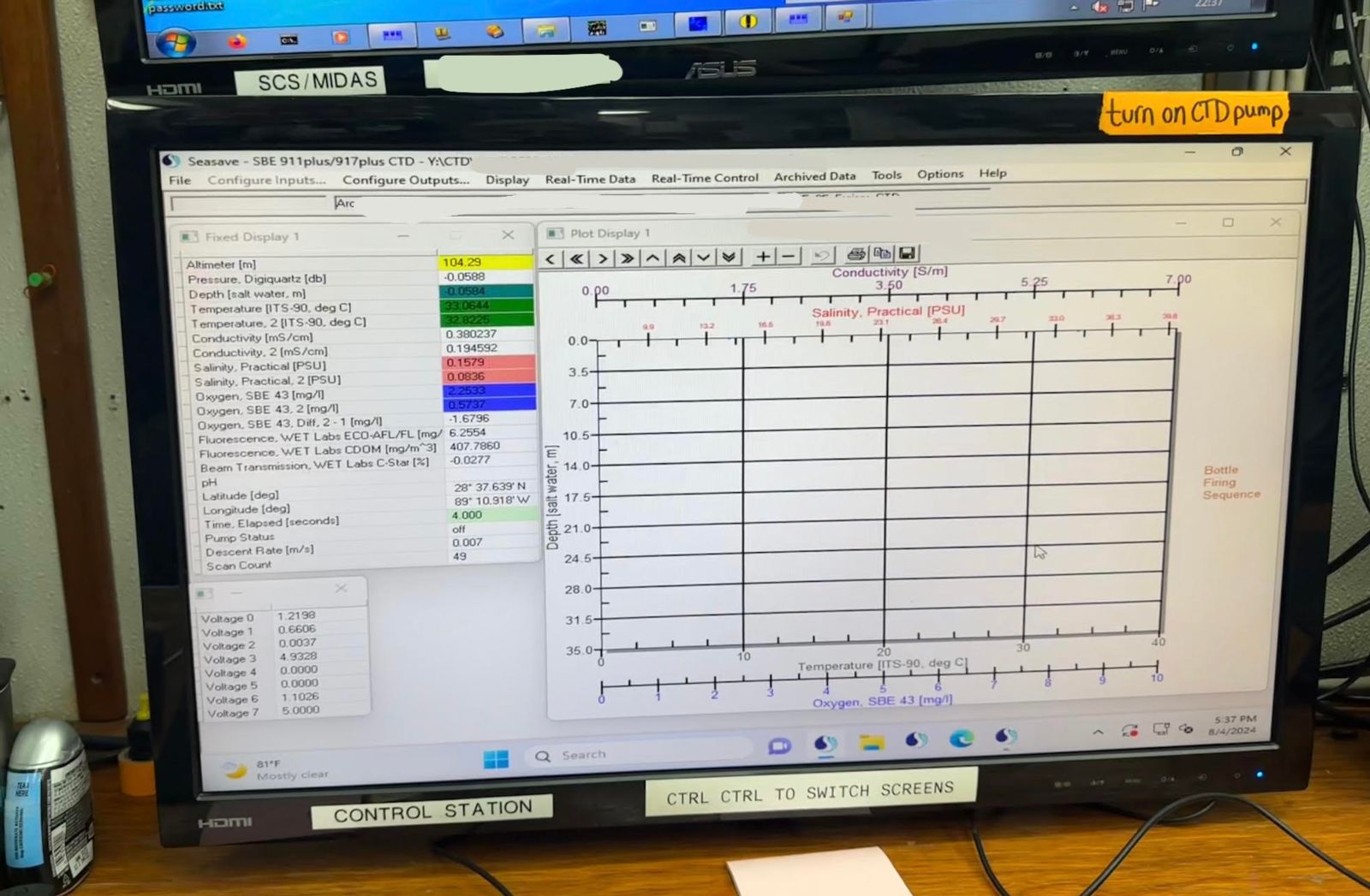

The science party departed the vessel at 08:00 CT on August 1st. From 08:00 to 14:00 CT, Maggie and I worked to address Wi-Fi network concerns, and practiced maintenance procedures for the CTD setup and Flow Through System to get them prepared for the next cruise. Alongside routine maintenance procedures, we also performed a Deck Test of the CTD as we had rearranged the instrument configuration. This was done because some sensors needed to be sent back to SeaBird, an oceanographic instrument manufacturer, to be recalibrated.

After 14:00 CT, we made our way to Houma Bollinger Shipyards. To those who aren’t familiar, this is the shipyard where the new Regional Class Research Vessels (RCRV) are being built! The three ships in this fleet are: R/V Taani, R/V Narragansett Dawn, and R/V Gilbert R. Mason. It was incredible to see this project in real life. Having read and heard so much about this program and the vessels being constructed, I was in awe while seeing it in person. In fact, I have an RCRV shirt that I was given through my position at the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s (OOI) Coastal Endurance Array. I brought it with me in hopes that I would get a glimpse of the R/V Taani at some point. I did not imagine that I would be able to visit the shipyard, let alone tour the inside the vessel!!!!

I am so grateful to all of the folks that made this tour possible, especially Kristin Beem. Thank you for staying after your work day had ended to give us a tour. I am glad that I was able to meet you, you are a force in the field. All of the information that you gave my group about the capabilities of the RCRVs will stay with me for a long time. I’m excited for the future of ocean research, and hope that I will be able to sail aboard them one day.

(I will try to make another blog post about what I learned on the tour itself! It will take me a while to write if it does happen:)).

Looking at the bows of the R/V Gilbert R. Mason (left) and R/V Narragansett Dawn (right)!

My RCRV shirt in front of the R/V Taani. (I don’t think I’ll ever get over being able to go and visit the R/V Taani while it was still under construction. It was an incredible experience!!

After an awesome port day of learning and visiting the shipyard where the RCRVs are being built, we completed the mobilization of the Pelican for the next cruise.

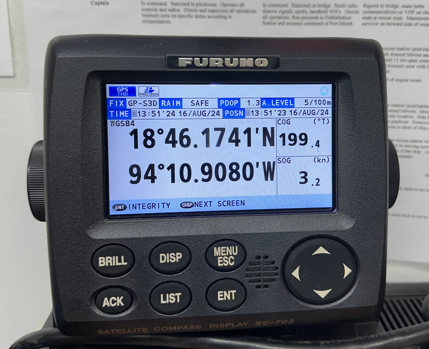

During this process, I successfully imported the station coordinates from UNOLS Cruise Planner into the navigational software that both the crew and science party use. I was proud of myself for being able to apply this knowledge, as this was a process I learned during the last cruise.

This new science party is deploying acoustic moorings throughout the Gulf of Mexico with the overarching goal of gaining a better understanding of the underwater soundscape of the region. If you’d like to learn more about this project, you can check out their website: https://sioml.ucsd.edu/.

We departed at 16:00 on August 2nd, the sunset as we left the dock was beautiful!

The sunset on our way out of the Bayou and into the Gulf!

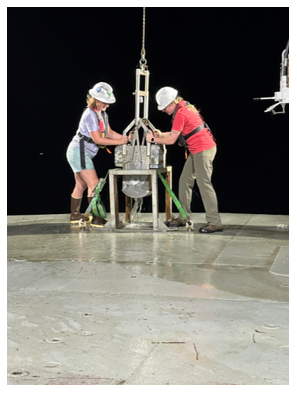

Next morning, the first recovery and deployment of the cruise was completed! I am excited to be learning more about deck operations during this cruise!

This was the first mooring that we recovered for the trip.

I’m excited to see what I will learn on this next cruise, talk to you next week! 🙂

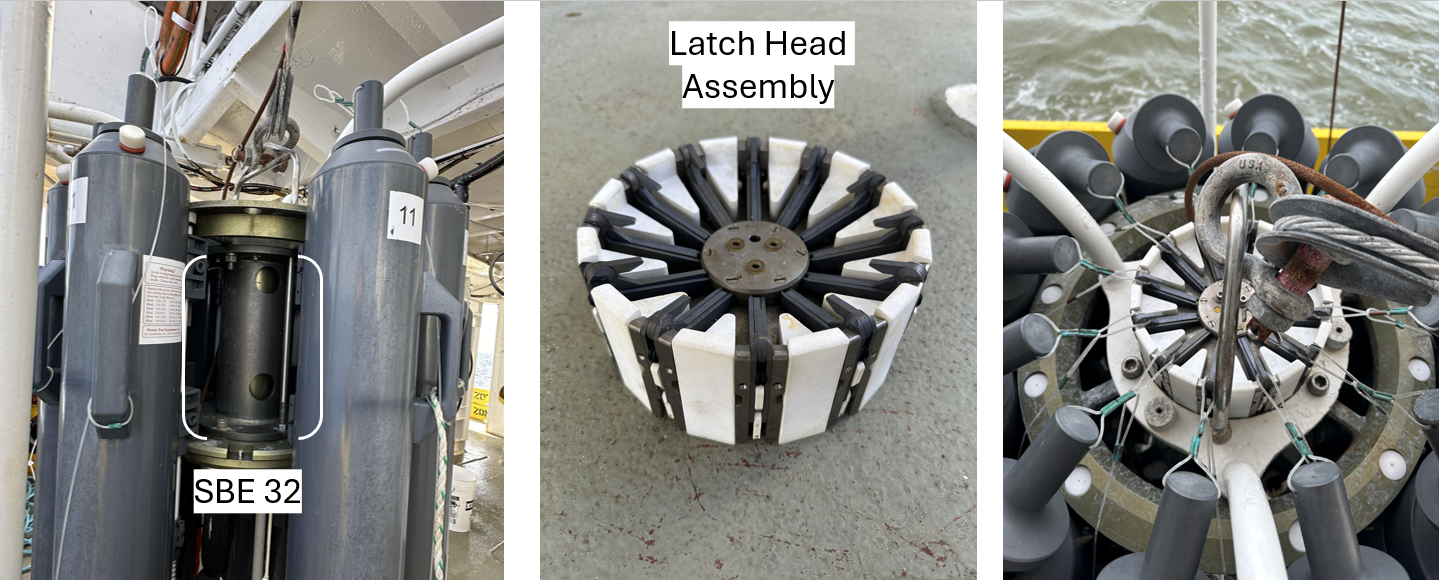

Here are what the SBE 32 and “latch head assembly” look like!

Here are what the SBE 32 and “latch head assembly” look like!

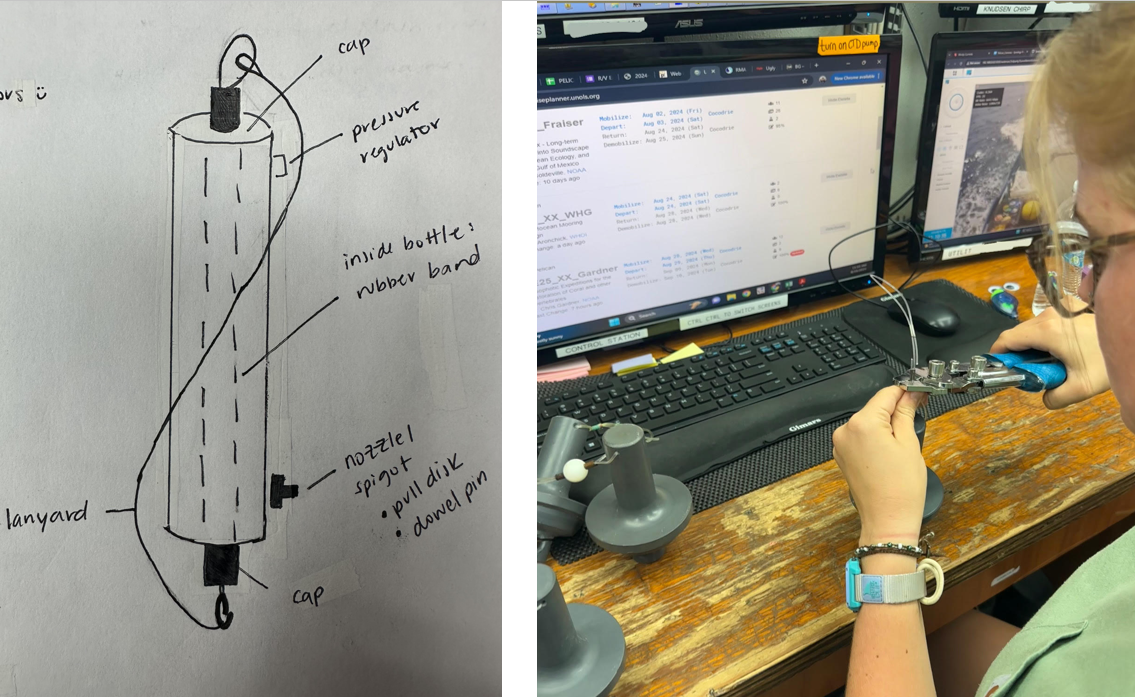

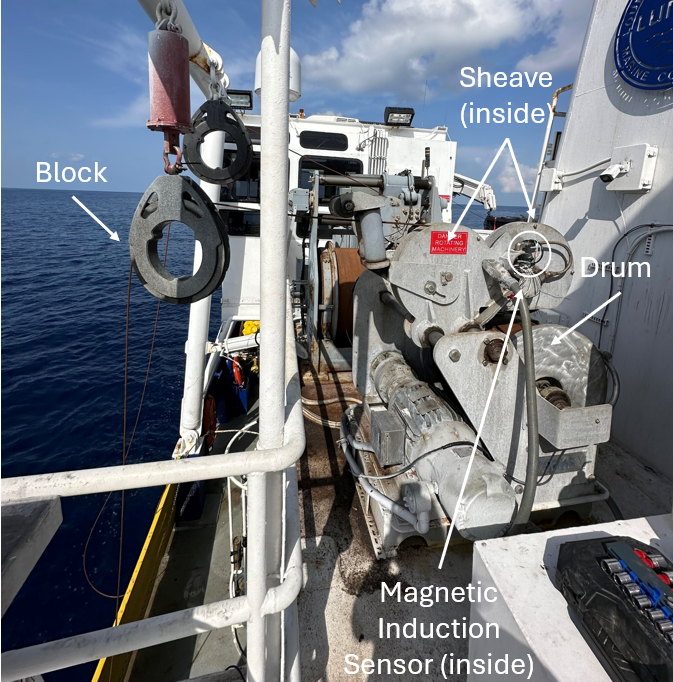

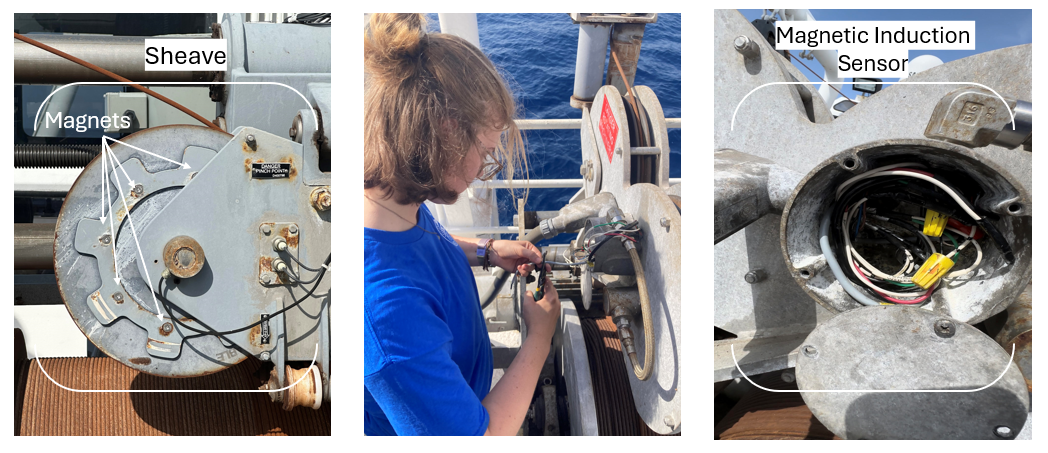

From left to right: A close-up image of the sheave, me installing the magnetic induction sensor, the magnetic induction sensor after being installed.

From left to right: A close-up image of the sheave, me installing the magnetic induction sensor, the magnetic induction sensor after being installed.